Muscat is still holding the fort on Panamagate. In an earlier post I had suggested that his strategy would be that of buying time and if that is still the case then we have entered the fatigue stage where, after having weathered the bulk of the storm, Muscat will be counting on the inability of the general public to keep up with the momentum of the scandal. He will, in fact, be hoping that the general sense of weariness and helplessness that our citizens have when confronted with politics will have a saving effect on himself and his government.

The latest polls do not suggest as much and the slide in trust ratings together with the fact that corruption leapt to the top of public concerns mean that the effects of Panamagate are here to stay for a while yet. The crucial bit here is that the snowball effect of Panamagate has meant that your average citizen’s distrust in politics and politicians was spread wider than the protagonists of that particular saga and that Malta finally caught up with the rest of the world when it started to question the operations of a whole class of politicians.

In fact one of the positive outcomes of Panamagate is the “coming out” of public disapproval of our political class and of the system that that very same class has created in order to survive and grow. While the party in opposition attempted to form a national rally inspired by and for the purposes of Panamagate it has become increasingly the case that the focus has shifted onto the wider issue of the rotten state of our political establishment and that includes the party in opposition itself.

Part of the reason for the aforementioned shift lies in the defensive tactics of a government under siege. The strategy of spin by Muscat required a dose of counter-accusations of supposed or alleged corruption in the rank and file of the Nationalist MPs. It was very evidently a deviation tactic aimed at distracting all and sundry from the very obvious fact that Mizzi’s and Schembri’s position were untenable without the need of further proof. What ensued was an open barrage of exchanges with no holds barred. Truth, morality, public interest, the state of the nation – they all became expendable pawns in the partisan dialogue of insults and accusations.

The No Confidence Motion

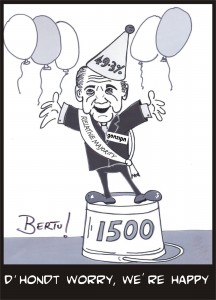

In the middle of all this the nationalist party moved a motion of no confidence in the government. We all know of the infamous 13 hour debate and what has been very aptly described as the vote that resulted in 38 likes. In the middle of this debate we had one very interesting talk delivered by former Minister Mallia. Much of what Mallia said or did not say merits analysis.

In the first place it was evident that rather than use his time to defend the government’s achievements or to defend Konrad Mizzi’s position, Mallia was intent to unleash his remaining anger leftover from Malliagate – the infamous shooting incident involving his driver that cost Mallia his cabinet position. His speech targeted those who in his words attack an honest politican who is intent on serving the country and who ends up losing his chance to serve thanks to these “attacks”.

Secondly Mallia was quick to ride his reputation of an experienced lawyer by referring to his faith in the “rule of law”. This not too subtle shifting of goalposts would have been missed by the man in the streets but was a clear attempt to alter the standards that were under scrutiny. Political responsibility is not the same as criminal or legal liability. Mallia was in a way pandering to Muscat’s idea that “proof” of illegal funds was needed in order to have to get rid of Mizzi (and Schembri) – the kind of proof one would expect in a trial in a court of law. Mallia is either naive or ignorant in that respect: it is evident to any constitutional lawyer that the very rule of law he claims to love would have Mizzi and Schembri out on their arses the moment the very set up of a company in Panama is discovered.

Finally, and most importantly, watching Mallia speak brought back memories of politicians from what is by now a very different era of politics. Back in 1992 a huge earthquake struck Italian politics: we all remember it as Tangentopoli (“Kick Back Gate” if you like). What began as a magisterial investigation in illegal funding of parties ended up being an expurgation of a whole political class (Operation Clean Hands).

Mallia’s speech focused very much on attacks on the truth and on the suffering of the “honest politician” who is not in politics money but to serve. In his words, “attacks” by journalists were damaging the opportunities of politicians to serve. This sounded very much like a muffled appeal to both sides of the house to moderate their terms because in the long run it is the very politicians on both sides who risk “suffering” the ignominy of an extirpation.

Back in 1992 Bettino Craxi, one of the gigantic figures of Italian politics, had stood up in the Italian Parliament shortly after the first scandals erupted and commented thus:

Su quanto sta accadendo la classe politica ha di che riflettere. (…) C’è un problema di moralizzazione della vita pubblica che deve essere affrontato con serietà e con rigore, senza infingimenti, ipocrisie, ingiustizie, processi sommari e grida spagnolesche. E’ tornato alla ribalta, in modo devastante, il problema del finanziamento dei Partiti, meglio del finanziamento del sistema politico nel suo complesso, delle sue degenerazioni, degli abusi che si compiono in suo nome, delle illegalita’ che si verificano da tempo, forse da tempo immemorabile. Bisogna innanzitutto dire la verita’ delle cose e non nascondersi dietro nobili e altisonanti parole di circostanza che molto spesso e in certi casi hanno tutto il sapore della menzogna.

Si è diffusa nel paese, nella vita delle istituzioni e della pubblica amministrazione, una rete di corruttele grandi e piccole che segnalano uno stato di crescente degrado della vita pubblica, uno stato di cose che suscita la piu’ viva indignazione, leggittimando un vero e proprio allarme sociale, ponendo l’urgenza di una rete di contrasto che riesca ad operare con rapidita’ e con efficacia.I casi sono della piu’ diversa natura, spesso confinano con il racket malavitoso, e talvolta si presentano con caratteri particolarmente odiosi di immoralita’ e di asocialita’.

E cosi’ all’ombra di un finanziamento irregolare ai Partiti e, ripeto, al sistema politico, fioriscono e si intrecciano casi di corruzione e di concussione, che come tali vanno definiti trattati provati e giudicati. E tuttavia, d’altra parte, cio’ che bisogna dire, e che tutti sanno del resto, e’ che buona parte del finanziamento politico e’ irregolare od illegale. I Partiti specie quelli che contano su apparati grandi, medi o piccoli, giornali, attivita’ propagandistiche, promozionali e associative, e con essi molte e varie strutture politiche e operative, hanno ricorso e ricorrono all’uso di risorse aggiuntive in forma irregolare od illegale.

Se gran parte di questa materia deve essere considerata materia puramente criminale allora gran parte del sistema sarebbe un sistema criminale. Non credo che ci sia nessuno in quest’aula, responsabile politico di organizzazioni importanti che possa alzarsi pronunciare un giuramento in senso contrario a quanto affermo: presto o tardi i fatti si incaricherebbero di dichiararlo spergiuro. (Bettino Craxi, June 1992).

That was at the outbreak of the scandal. The kickbacks that were investigated involved first and foremost the major political parties that had enjoyed a system of “democratic alternation” but that had developed a network of corrupt practices that later would be found to have overspilled in the business community. Political party kickbacks were parallel to grafts taken by individual politicians and the links spread straight into the arms of criminal activity. In his early defence in 1992, Craxi stressed that (I paraphrase) “the illegal funding of the political system (no matter how many negative judgements and reactions it may have generated) cannot be and cannot be used as an explosive to blow up a whole system, to delegitimize a political class, to create a climate where neither corrections nor an effective cleansing action can arise but only disintegration and adventure. For this situation we need a remedy, actually more than one remedy.”

I cannot help but noticing that Mallia’s impassioned apology for the workings of politicians in spite of what he perceives as “attacks” on their operation has inspirations that are rooted in the interventions of Craxi and politicians of his ilk back in 1992. 10 months later, in April 1993, Bettino Craxi was faced with a number of requests by the magistratura for authorisation to proceed (against him in court) and he had to make one last impassioned defence before the Camera dei Deputati. Almost 23 years ago to the day he stood up to make one of the longest speeches in defence of a failed system.

Si e’ invece fatto strada con la forza di una valanga un processo di criminalizzazione dei partiti e della classe politica. Un processo spesso generalizzato ed indiscriminato che ha investito in particolare la classe politica ed i partiti di governo anche se, per la parte che ha cominciato ad emergere, non ha risparmiato altri come era e come sara’ prima o poi inevitabile. (…) Ma di tutte l’erbe s’e’ fatto alla fine un fascio.

Tutto si è ridotto ad una unica accusa generalizzata. Le campagne propagandistiche hanno ruotato sovente solo attorno a slogans ed a brutali semplificazioni. Di questo si è incaricata infatti parte almeno della stampa e dell’informazione, andando ben al di là dei diritti e dei doveri propri dell’informazione, deformando spesso oltre misura, esaltando le ragioni dell’accusa e mettendo di canto quelle della difesa, travolgendo senza alcun rispetto diritti costituzionalmente garantiti con difese divenute praticamente impossibili, creando sovente un clima infame che ha distrutto persone, famiglie e generato tragedie.

La criminalizzazione della classe politica, giunta ormai al suo apice, si spinge verso le accuse piu’ estreme, formula accuse per i crimini piu’ gravi, piu’ infamanti e piu’ socialmente pericolosi. Un processo che quasi non sembra riguardare piu’ le singole persone, ma insieme ad esse tutto un tratto di storia, marchiato nel suo insieme. Un vero e proprio processo storico e politico ai Partiti che per lungo tempo hanno governato il Paese. (29th April 1993)

The echoes in Mallia’s speech 23 years later are incredible. It does not stop with Mallia mind you, even though Mallia’s speech was the most transparent in this respect. Politicians under attack for their unethical performances will ask you to be positive and focus on “all the good we have done” that cannot and should not be overshadowed by what they claim to be “slips of human error”. This spin is current today and it is no surprise that it was just as current in Craxi’s day.

Tutti i cicli, come è naturale passano, entrano in contraddizione, si esauriscono, degenerano. Sono cosi’ subentrati gli anni delle difficolta’ e della crisi, che stiamo ancora attraversando. Ma gli effetti e le conseguente di un periodo critico sarebbero stati ben diversi e ben piu’ onerosi se non avessimo avuto alle spalle il solido sviluppo realizzato nel corso degli anni ottanta ed un retroterra conquistato con un balzo in avanti poderoso.

It did not come without an admission though. Craxi’s line of reasoning was that parties have always been funded in a questionable manner and that this should not preclude an acknowledgement that they have functioned for the good of the state.

Cosi’ come nella vita della societa’ italiana non e’ nata negli anni ottanta la corruzione nella pubblica amministrazione e nella vita pubblica.

La vicenda dei finanziamenti alla politica, dei loro aspetti illegali, dei finanziamenti provenienti attraverso le vie piu’ disparate dell’estero, della ricerca di risorse aggiuntive rispetto poi ad una legge sul finanziamento pubblico ipocrita e ipocritamente accettata e generalmente non rispettata, accompagna la storia della societa’ politica italiana, dei suoi aspri conflitti, delle sue contraddizioni e delle sue ombre, dal dopoguerra sino ad oggi.

Non c’e’ dubbio che un troppo prolungato esercizio del potere da parte delle piu’ o meno medesime coalizioni di Partiti ha finito con il creare per loro un terreno piu’ facilmente praticabile per abusi e distorsioni che si sono verificate. Ma onestà e verità vorrebbero che in luogo di un processo falsato, forzato, ed esasperato, condotto prevalentemente in una direzione, si desse il via ad una ricostruzione per quanto possibile obiettiva ed appropriata di tutto l’insieme di cio’ che è accaduto.

Si tratta di una realta’ che non si puo’ dividere in due come una mela, tra buoni e cattivi, gli uni appena sfiorati dal sospetto, gli altri responsabili di ogni sorta di errori e nefandezze.

The appeal to morality and honesty in such times becomes almost an automatic reflex. I have already mentioned how jarring the appeal to “honest Maltese” was prior to the first rally in Valletta. This tendency to transform a political discussion into a dichotomy between “good and evil” is dangerous – dangerous both for the interlocutors who have suddenly arrogated unto themselves the questionable position of absolute purity as well as for the confused electors who are unable to detach themselves from the call of partisan loyalty when assessing such circumstances.

In this I will refer once again to Craxi’s swan song. In the heat of the affair, prior to his exposure to the courts and his subsequent self-imposed exile in Hammamet (Tunisia) he made one final appeal to a good sensed reform devoid of revolutionary lynch mobs. It sounds eerily relevant to today’s world:

Non credo del resto che la moralizzazione della vita pubblica possa esaurirsi con la denuncia ed il superamento dei sistemi di finanziamento illegale dei Partiti e delle attività politiche e con la condanna di tutte le forme degenerative che ne sono derivate. Non credo che solo in questo consista la questione della corruzione della vita pubblica. Non credo che il procedere in modo violento con l’inevitabile inasprimento dei traumi e dei conflitti che ne scaturira’ potra’ aprire un periodo ordinato e rigoglioso nella vita democratica. Non credo che per queste vie li Paese si incamminerà verso un periodo di rinascita economica,di riequilibrio sociale,di un rinnovamento politico ed istituzionale all’insegna di un grande decentramento dei poteri, nel consolidamento dell’unita’ della Nazione,e insieme di riconquista di un prestigio internazionale tanto piu’ necessario quanto piu’ aspre si vanno facendo la competizione e la conquista di aree di influenza nel mondo. C’e’ un problema democratico di rinnovamento e di ricambio della classe politica dirigente, c’è un problema di alternanza di forze nelle responsabilità di guida e di governo.

E’ un problema che deve essere risolto democraticamente, nel modo piu’ trasparente e diretto, senza provocare il soffocamento del pluralismo politico e senza fare ricorso alla barbarie della giustizia politica. Una politica che fosse intrisa di demagogia e di ipocrisia, non sarebbe destinata a fare lunga strada. Cosi’ come non e’ destinato a farla chi ancora oggi continua a non usare il linguaggio della verità, per non parlare di chi si presenta di fronte al paese con l’aria smemorata, con i tratti di chi non sapeva anche cio’ che avrebbe dovuto inevitabilmente sapere, di chi ha vissuto sino a ieri in preda a superficiali distrazioni, di chi denuncia nomenklature, ignorando la propria di cui continua a portare tutti i caratteri, e dimenticando il proprio ruolo, la propria responsabilità, di chi addirittura giudica dall’alto delle sue frequentazioni malavitose.

These quotes may be lengthy but they are necessary in order to have a look at the lessons that history provides us. It is very probable that by the time Craxi gave this speech he knew he would have little time left within the political sphere. His April 1993 speech would actually win him time as he would win that vote and stay out of the courts until December of that year when his prosecution was finally authorised. By May 1994 he was fleeing to Tunis to escape jail and where he would live till his death in 2000 under the protection of Tunisia’s leader Ben Ali (himself ousted in 2011 and charged with money laundering and drug trafficking sentenced to 35 years).

Lessons

Craxi’s story serves to remind us of how a political class will struggle and fight tooth and nail to survive. The defences it will put forward will rarely be different through the ages. In a system such as ours that has also been molded to allow for alternation between different networks of power we run the risk of seeing much of the same.

Unfortunately Malta does not have a strong judiciary or watchdogs. Konrad Mizzi and Keith Schembri have still not gotten so much as a slap on the wrist from anyone. Our tax authorities are proceeding at a slow pace but that is not even the point because tax authorities are not about political responsibility. Our Prime Minister hides behind a tax audit spirited out of one of his fantastical speeches full of management words but no political consequences. Our political parties – both of them – still inhabit a world where massive financing is taken as a basic requirement for their operation. No one questions whether paring down their size would be a good thing in itself.

We will continue to hear stories and accusations and counter-accusations of graft, politicla favours, political networks. In the meantime Malta lacks the momentum that existed in Italy under the system of aggressive togas or in Iceland with an aggregation of popular sentiment that could result in a proper change.

I will conclude by referring you once again to Mallia’s speech and his defence of the privacy of the honest politician. One of the “victims” of tangentopoli was a socialist member of the camera deputati. His name was Sergio Moroni and when faced with more avvisi di garanzia he decided to take his life, not before leaving an impassioned appeal addressed to the President of the Chamber (ex-President Giorgio Napolitano). At the risk of infuriating the readers with the length of this post I am reproducing his letter below.

Se vogliamo che tutto rimanga lo stesso, bisogna che tutto cambi.

« Egregio Signor Presidente,

ho deciso di indirizzare a Lei alcune brevi considerazioni prima di lasciare il mio seggio in Parlamento compiendo l’atto conclusivo di porre fine alla mia vita. È indubbio che stiamo vivendo mesi che segneranno un cambiamento radicale sul modo di essere nel nostro paese, della sua democrazia, delle istituzioni che ne sono l’espressione.Al centro sta la crisi dei partiti (di tutti i partiti) che devono modificare sostanza e natura del loro ruolo. Eppure non è giusto che ciò avvenga attraverso un processo sommario e violento, per cui la ruota della fortuna assegna a singoli il compito delle “decimazioni” in uso presso alcuni eserciti, e per alcuni versi mi pare di ritrovarvi dei collegamenti. Né mi è estranea la convinzione che forze oscure coltivano disegni che nulla hanno a che fare con il rinnovamento e la “pulizia”. Un grande velo di ipocrisia (condivisa da tutti) ha coperto per lunghi anni i modi di vita dei partiti e i loro sistemi di finanziamento. C’è una cultura tutta italiana nel definire regole e leggi che si sa non potranno essere rispettate, muovendo dalla tacita intesa che insieme si definiranno solidarietà nel costruire le procedure e i comportamenti che violano queste regole.

Mi rendo conto che spesso non è facile la distinzione tra quanti hanno accettato di adeguarsi a procedure legalmente scorrette in una logica di partito e quanti invece ne hanno fatto strumento di interessi personali. Rimane comunque la necessità di distinguere, ancora prima sul piano morale che su quello legale. Né mi pare giusto che una vicenda tanto importante e delicata si consumi quotidianamente sulla base di cronache giornalistiche e televisive, a cui è consentito di distruggere immagine e dignità personale di uomini solo riportando dichiarazioni e affermazioni di altri. Mi rendo conto che esiste un diritto d’informazione, ma esistono anche i diritti delle persone e delle loro famiglie. A ciò si aggiunge la propensione allo sciacallaggio di soggetti politici che, ricercando un utile meschino, dimenticano di essere stati per molti versi protagonisti di un sistema rispetto al quale oggi si ergono a censori.

Non credo che questo nostro Paese costruirà il futuro che si merita coltivando un clima da “pogrom” nei confronti della classe politica, i cui limiti sono noti, ma che pure ha fatto dell’Italia uno dei Paesi più liberi dove i cittadini hanno potuto non solo esprimere le proprie idee, ma operare per realizzare positivamente le proprie capacità e competenze. Io ho iniziato giovanissimo, a solo 17 anni, la mia militanza politica nel Psi. Ricordo ancora con passione tante battaglie politiche e ideali, ma ho commesso un errore accettando il “sistema”, ritenendo che ricevere contributi e sostegni per il partito si giustificasse in un contesto dove questo era prassi comune, ne mi è mai accaduto di chiedere e tanto meno pretendere.

Mai e poi mai ho pattuito tangenti, né ho operato direttamente o indirettamente perché procedure amministrative seguissero percorsi impropri e scorretti, che risultassero in contraddizione con l’interesse collettivo.

Eppure oggi vengo coinvolto nel cosiddetto scandalo “tangenti”, accomunato nella definizione di “ladro” oggi così diffusa. Non lo accetto, nella serena coscienza di non aver mai personalmente approfittato di una lira. Ma quando la parola è flebile, non resta che il gesto.

Mi auguro solo che questo possa contribuire a una riflessione più seria e più giusta, a scelte e decisioni di una democrazia matura che deve tutelarsi. Mi auguro soprattutto che possa servire a evitare che altri nelle mie stesse condizioni abbiano a patire le sofferenze morali che ho vissuto in queste settimane, a evitare processi sommari (in piazza o in televisione) che trasformano un’informazione di garanzia in una preventiva sentenza di condanna. Con stima.

Sergio Moroni »