Identifying Lou Bondi’s pitch on Tuesday’s Bondi+ was not too difficult. Franco Debono is doing a good enough job of undermining any valid points he may have with his behavioural shifting from the conspiracy theorist to the unabashedly ambitious politician. Franco seems to be unable to reconcile the values of his political mission with his unbridled hunger to slither up the greasy ladder of power as we know it. His behaviour plays into the hands of the spin-doctors of “taste” who are prepared to highlight his faux pas until they totally eclipse any reasonable matter he may rightly wish to bring onto the forefront of the national agenda.

Bondi desperately tried to pitch the Franco vs Gonzi angle repeatedly throughout the program – infamously culminating in Franco’s refusal to “parrot” the words that the anchorman (and Nationalist quasi-candidate endorser) had desperately tried to plant in his nervous interlocutor’s mouth all evening. One aspect of this angle pitched by Bondi was his continued insistence that Franco was way out of his rights when he threatened to bring down this government by withholding his confidence vote when the time comes.

In a little “f’hiex tifhem?” (a very typical Maltese challenge of “what’s your expertise in this”) moment Bondi referred to his university lecturing credentials (“I taught politics and not just sociology – ghandek zball madornali“) presumably inspired by Franco’s earlier stunt of using his school reports. For a second I was worried that the two would pull down their pants and compare the size of their private members (sic) but a little side jab about the “Santana booing incident” (as witnessed from the I’m A VIP Quasi-Minister section of the crowd) did the trick.

Back to the constitution.

For it is a constitutional issue we are talking about. Does a lone MP from the parliamentary group of the party in government have the right to threaten to bring down the government? In bipolar (sorry, bipartisan) Malta we tend to run off with the idea that the game is one of simple mathematics – you win an election, you have the autocratic right to govern (should I say Oligarchic Franco?). Sure, what with the pilfering and tweaking of the electoral laws we have perfected the English constitutional bipartisan system to perfection and driven more than one death blow to the possibility of proportional representation.

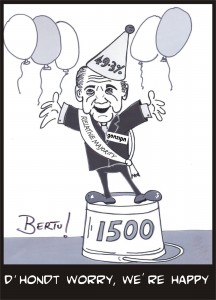

Last election’s carcades were hooting to the tune of a D’Hondt majority (see Bertoon illustration that we cooked up the next day). the D’Hondt system of voting combined with our “tweaked” constitutional provisions had led to a relative majority government – no party had obtained more than 50% of the votes but one party had 1,500 votes than the other. A constitutional clause had come into play and the way it worked was –

a) if only two parties are elected to parliament,b) if none of the two parties obtain more than 50% of the votes,then the party with the largest number of votes (a relative majority) will be entitled to an adjustment of seats in order to be able to enjoy a majority of seats in parliament. That’s all found in article 51(1)(ii) of the Constitution of Malta.

Interestingly (and useful for later discussion) the provisos to this article are a rare instance in which reference is made directly to “political parties”. It’s interesting because the Constitutional structure relating to representation and government (and therefore to the management of the basic power entrusted by “the people”) centres around individual “representatives” as elected to parliament by universal suffrage. The constitutional link between elector and elected is direct – there was no original intention for the intermediaries we now call “political parties”*.

This important distinction between political parties and members can be clearly seen from the Constitutional article on the appointment of the Prime Minister – article 80:

Wherever there shall be occasion for the appointment of a Prime Minister, the President shall appoint as Prime Minister the member of the House of Representatives who, in his judgment , is best able to command the support of a majority of the members of that House (…)

Again. No parties. The President takes one good look at the House of Representatives and determines whether any member among them can count on “the support of a majority of the members” – that’s what is in play whenever a “confidence vote” comes into play. It’s an opportunity to put to test whether the PM still enjoys that majority support. In the current context it’s what Joseph Muscat would like to table (a motion of confidence) and where Franco’s threat might come into play (by not voting for the PM and thus undermining his ability to “command the support of a majority”.

Now comes the hard part for hardcore nationalist voters to digest. Franco Debono is the latest symptom of the Coalition of the Diverse called GonziPN that oh-so-miraculously snatched victory from the jaws of defeat last election. The rainbow coalition within GonziPN was possible because of a lack of scrutiny, a loose combination of values (if any) and mainly because any candidate who could steal valuable votes that could lead to the relative majority victory (and therefore to the automatic majority in parliament) was backed to the hilt. Remember the JPO saga? Remember the spin masters backing what was very evidently a loose gun to the hilt – basta nitilghu?

So when the members of parliament finally took their place in the house of representatives Lawrence Gonzi could assume that he commands the support of the majority of members. He assumed it because any leader of a political party in Malta who has just won the election assumes that his party members will back him to govern. Easy. Alfred Sant assumed that in 1996. Lawrence Gonzi had no reason not to in 2008. The mechanism is not foolproof however. At the basis of the whole system remains the basic currency of power transfer – the representatives themselves. As Franco has reminded us more than once the “support of the representatives” cannot be taken for granted.

The mechanism of “support” or confidence is a check on the power of government. Viewed from outside the convoluted scenario that Franco has created around himself (with the help of the bloodsucking media) you will understand that the right of a member to withdraw his support is an important check in our democracy. It is just as important (if not more) as the existence of an opposition.

Even though our political parties operate on the assumption that “loyalty” is universally automatic they have now been exposed to the democratic truth that it is not. The failure is not of the system but of the arrogant assumption that the bipartisan mechanisms that the parties have written into the constitution will guarantee their permanent alternation. Franco’s methods might be obtuse and distasteful especially when they betray blatant and crude ambition but on a political level the renegade politician who disagrees with the party line was not only predictable but threatens to become a constant in the future.

The more political parties ignore the need to be coherent politically and the more they just throw anything at the electorate in the hope that something bites the more they can expect of “Franco-like” personalities. The failure to whip Franco into the party line is not a democratic failure or a constitutional flaw but a failure of the political party to operate as an effective vehicle of democratic representation.

D’hondt worry? Frankly it was only a matter of time. It’s actually a miracle it took this long for the shit to hit the fan.

* In a recent House of Commons document (Speaker’s Conference on Parliamentary Representation) political parties were defined as “the mechanism by which people of any background can be actively involved in the tasks of shaping policy and deciding how society should be governed. While they are not perfect organisations they are essential for the effective functioning of our democracy. Without the support of political parties it would be difficult for individual Members of Parliament, as legislators and/or as members of the Executive, to organise themselves effectively for the task of promoting the national interest—including by challenge to the Government, where that is necessary and appropriate—and ensuring that proposed new laws are proportionate, effective and accurately drafted.”

8 replies on “That Constitutional Question”

Back with a bang. Awesome.

Loved the second bit of your writing. (the first bit was a polite way of saying you dislike FD).

I’m totally in favour of the right of a member to withdraw his support to his party! When i vote, i vote for candidates not for a party, so i ask the candidate to represent me by the access given to him by the party.

I don’t see that as a threat to the future. Hopefully it does become constant so that no man in the helm of a party will ever think that he/she can repeat political mistakes without being questioned by his own team members!

The problem with Malta is that we have the majority of the population who votes for one of the TWO parties. That means, i cannot vote an independent candidate (something i would love to do) and hope he gets in Parliament as it’s only through the Parties that they can make it into the structure.

FD stated that clearly when he insisted he wouldn’t be elected as an independent candidate and thus he made it through the PN. That doesn’t mean he had to nod for each and every situation within the party – even though 99% of the population assumes it should be like that!

Can’t we have a “jacques-in-pillole” version for us ignorant plebs, pretty please? ;)

ps. welcome back

In examiner mode, so here are my pedantic comments:

Is it not evident that Art 51(1) is intended to grant the party that won a relative majority the ability to govern? Does it not follow that there is a direct link between electoral outcomes and expected behaviour of MPs? Does it also not follow that MPs should support the party on whose ticket they were elected except in extreme circumstances? Do such extreme circumstances exist in the present situation?

Hiya JBB. You ask about whether it is evident. The issue of government is inextricably linked with article 80 and the choice of a Prime Minister (the first step that leads to the selection of a cabinet by the same). As I pointed out, this fundamental governance article to this day omits any reference to parties – the inference (or evidence) here points to the basic tenet of a representative house majority (independently of the parties).

Article 51 and more particularly its provisos undeniably introduces the element (historically at a later stage) of political parties. All your conclusions are possible but not absolute. Yes article 51(1)’s provisos were intended to facilitate the situation for parties to fulfil the “support of the majority” requirement where possible. Yes there is an implied contract between an MP elected on a party ticket and his electorate. Does it follow that MP’s should support the party etc? That last step is a logical leap. It COULD follow, it SHOULD follow but it is not an absolute rule.

Particularly in this case you have to see whether the party role in the implied contract between MPs and their voters has been fulfilled. The party role is as a guarantee of values and effective organisation. If an MP does not feel bound by the party ties at a certain point we should most certainly look at his obligations towards the party but we should not neglect the matter whether the party has failed in its set up – probably by taking its MPs and their votes for granted.

Which is why article 51 does not exist in a vacuum and must be read in conjunction with the strong implication of article 80 – where the ultimate crystallisation of transfer of power from universal suffrage to parliamentary support is brought into effect – without any role for political parties.

(ASIDE – Imagine a coalition situation. The “party ticket” issue becomes even more irrelevant. Technically the government is formed by the Member (leader of party) who enjoys a majority formed across party lines. Party loyalty is a separate issue there – and an even more glaring example than the current one as to why the support of a parliament member for government cannot be taken for granted).

Jacques, the thing is I don’t think there’s any other way art. 80 could have been formulated in any other way, even if our Constitution were not “party-oblivious”, as most of it is.

Secondly, if the link between the electors and the MPs is so direct how would a party financing law be conceptually admissable? (Note, I say “conceptually” not “legally”).

Dom Mintoff was one of the architects and a prime protagonist of the old system. Yet he rebelled because he could not stomach what he saw as a new party no longer cast in his own image and because he hated its leader. Franco Debono is more overtly acting out of his own selfish interests.

They are two of a kind; both them mavericks who took advantage of the unouq power the electoral result bestowed on them.

What they have in common – and the real reason for the shenanigans they caused is a gigantic ego.

[…] That Constitutional Question Even though our political parties operate on the assumption that “loyalty” is universally automatic they have now been exposed to the democratic truth that it is not. The failure is not of the system but of the arrogant assumption that the bipartisan mechanisms that the parties have written into the constitution will guarantee their permanent alternation. Franco’s methods might be obtuse and distasteful especially when they betray blatant and crude ambition but on a political level the renegade politician who disagrees with the party line was not only predictable but threatens to become a constant in the future. […]